Published

Nov 30, 2025

Linh Nguyen

Building a successful consumer mobile app is hard.

Just last year alone, over 1.1 million new apps were published on the app stores. Yet fewer than 5% reached $5,000 in monthly recurring revenue. The app stores are fiercely competitive, and of those who launch, very few actually make money.

But it's also incredibly rewarding to build something that helps transform the lives of millions – whether that's helping them learn a language (Duolingo), sleep better (Calm), or stay fit (Strava).

If you're embarking on this exciting yet challenging journey, my goal is to give you an actionable framework to get there. This four-part playbook is based on what I've learned as an early hire at Blinkist as the company scaled from 0 to 25 million users over the course of a decade. It also draws on lessons from 8 of the most successful consumer mobile app companies (Duolingo, Instagram, Uber, Airbnb, Calm, Pinterest, DoorDash, ReciMe)

Today I'm incredibly lucky to be working alongside a community of mobile app founders as I'm building Rey, a platform for building and launching mobile apps visually. This playbook is not a guarantee of success, but it will be a great starting point for anyone building consumer mobile apps.

Here's what's in store:

Step 1 - How to find and validate your app idea (←You're here)

Step 3 - How to get your first 100 paying customers (coming soon)

Step 4 - How to build your app growth engine (coming soon)

So let’s get started.

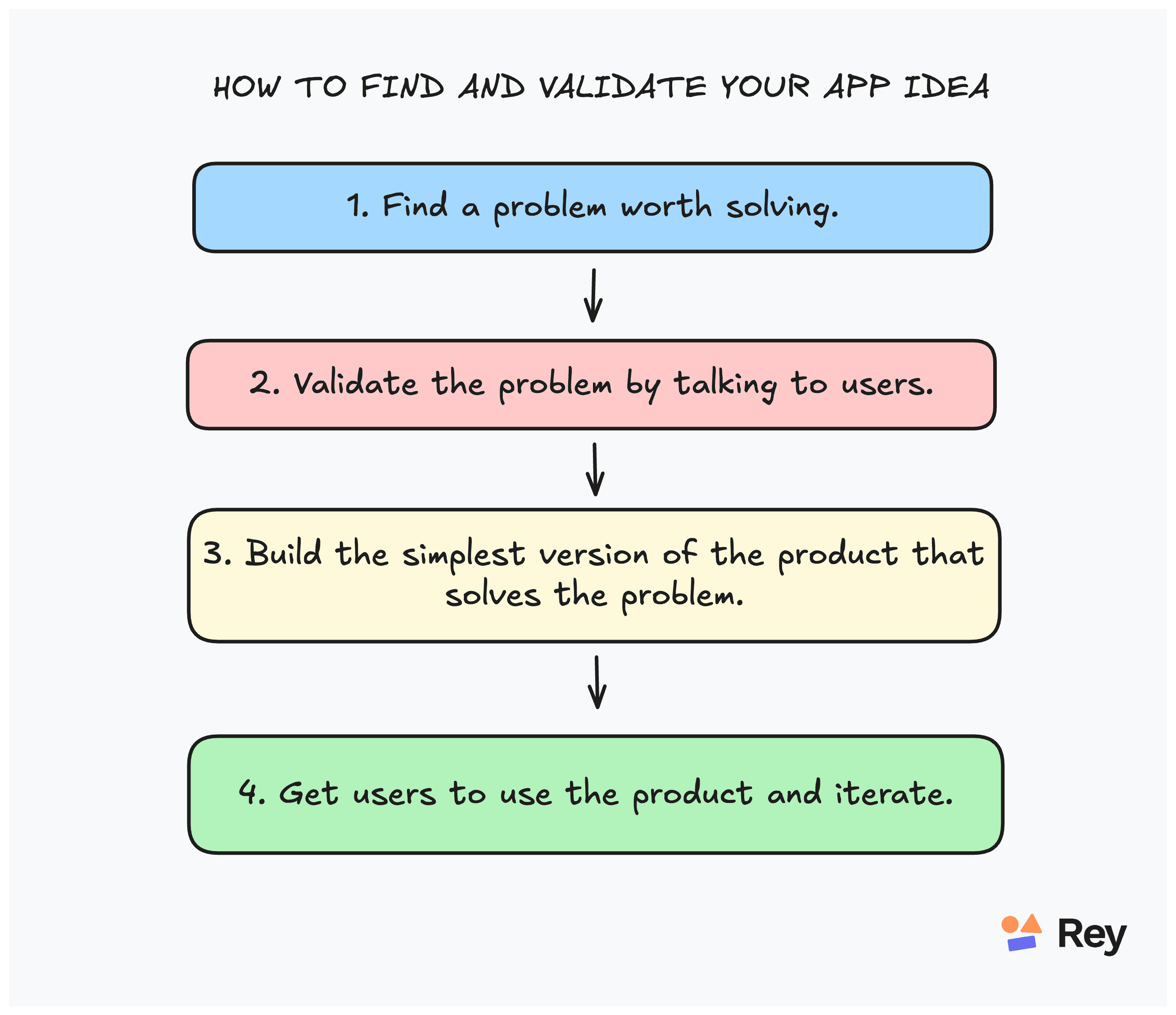

Based on my experience at Blinkist and what I learned from other successful mobile app founders, here's a framework for how to find and validate your idea:

1. Find a problem worth solving

Start with a problem you (or someone around you) experience. It's really important that it's a problem you truly care about and deeply understand.

No matter which problem you're going to work on, you're not going to be the first person to ever tackle it. It's very likely that many others have tried and failed before. You're going to experience a lot of setbacks and challenges along the way.

Finding product-market fit is hard. Unless you're truly excited about the problem, almost to the point of obsession, you're going to give up before you can get there.

Strategy #1. Start with a problem you've experienced firsthand

Michael Acton Smith started Calm with Alex Tew after having struggled for years with stress and burnout as a serial entrepreneur.

"And the key breakthrough for me was when I did something I’d never done before: I took myself off on a solo holiday. I went away to the Austrian Alps to this kind of resort where I played tennis in the morning, I scribbled in my notebook, I read books, and I started to try to meditate because I’d heard about it.

And it was just incredible. The fog started to clear. I’d had my face pushed up against the cliff and couldn’t see a way out of this problem that I was facing with my business. Just taking a step back and getting perspective was hugely valuable. I read a bunch of books and research papers, and I realized that this is science: mindfulness is a way of rewiring the human brain. What if we could make this simple and relatable and accessible to everyone? This could be one of the biggest opportunities and businesses in the world."

– Michael Acton Smith (Calm) via Diary of a CEO

Luis Von Ahn grew up in Guatemala, where there's limited access to education. So when he was choosing a PhD project with Severin Hacker, which eventually became Duolingo, he knew he wanted to work on something that makes education accessible to more people.

"We wanted a PhD project for him, and I thought, "Well, you know, I really am passionate about education. Let’s try to do something related to education." Now my views on education have always been very influenced by where I’m from because I’m from Guatemala, and it’s a very poor country.

Now the thing about Guatemala is in poor countries a lot of people say that education is the thing that can bring equality to the different social classes, but I always saw it as quite the opposite. I always thought that education actually was something that brought inequality. Because what happens is the people who have money can buy themselves the best education in the world, and because of that they remain having a lot of money, whereas the people who don’t have very much money barely learn how to read and write and therefore remain not having very much money. So I wanted to do something with education that would give equal access to everybody."

– Luis Von Ahn (Duolingo) via The Tim Ferris Show

Strategy #2. Start with a community you deeply understand

If you're struggling to think of a problem, consider a target group you deeply care about — for example, small business owners, remote workers, freelancers, parents, caregivers, athletes, musicians, or people managing chronic health conditions.

Tony Xu and the founders of DoorDash knew they wanted to build something that helped small business owners be more successful. He grew up in Illinois, and one of the ways he spent time with his mom as a child was working alongside her in a Chinese restaurant.

"All of us have our own stories in terms of why we have an affinity towards small businesses. Mine happens to be personal in that I have a connection to a small business that my mom ran. I grew up in Illinois, and one of the ways in which I hung out with my mom as a child was actually working alongside her inside of a Chinese restaurant where she worked in Champaign. And so, I’ve always had an affinity towards, how do you help these underdogs who don’t really view their businesses as a profession; they view it really as a lifestyle. How do you help them be successful?

The idea for DoorDash actually didn’t come right away. We spoke with three or four hundred small businesses across pretty much every category – retail, restaurants, services. And the main question we asked them was, "Tell us about all of the activities that you do every day." I think it was a lot easier to see a specific problem in plain sight than to try our best to interpret a generic answer of what might be a challenge for them."

– Tony Xu, DoorDash via Crucible Moments

2. Validate the problem by talking to users

Talk to at least 10 people who experiences the problem. Oftentimes they will also become your first users.

How do you find your first users? A good starting point is your friends, family, or people you worked with. If you have a deep understanding of who you are building for, it's quite natural to think of a few places where they often hang out, online or in real life.

If you're building for parents, you might find them in parenting Facebook groups, local playgrounds, or school pickup lines. If you're targeting freelancers, try co-working spaces, LinkedIn groups, or Reddit communities like r/freelance. For fitness enthusiasts, look at Strava clubs, CrossFit gyms, or running clubs. The key is to go where your target users already gather.

Don't be shy about reaching out directly. Send personal messages saying you're researching how people deal with [specific challenge or area] and would love to learn about their experience. Most people are surprisingly willing to chat if you're genuinely interested in understanding their challenges rather than pitching them something.

Once you've found people to talk to, there are two main ways to learn from them:

Strategy #1. Do user interviews

What should you ask in these interviews? By talking to these users, you're trying to understand these questions:

Do they actually experience the problem that you have in mind?

How painful is the problem? Have they actually tried to look for a solution? If not, why?

If they have tried a solution, what worked and what didn't?

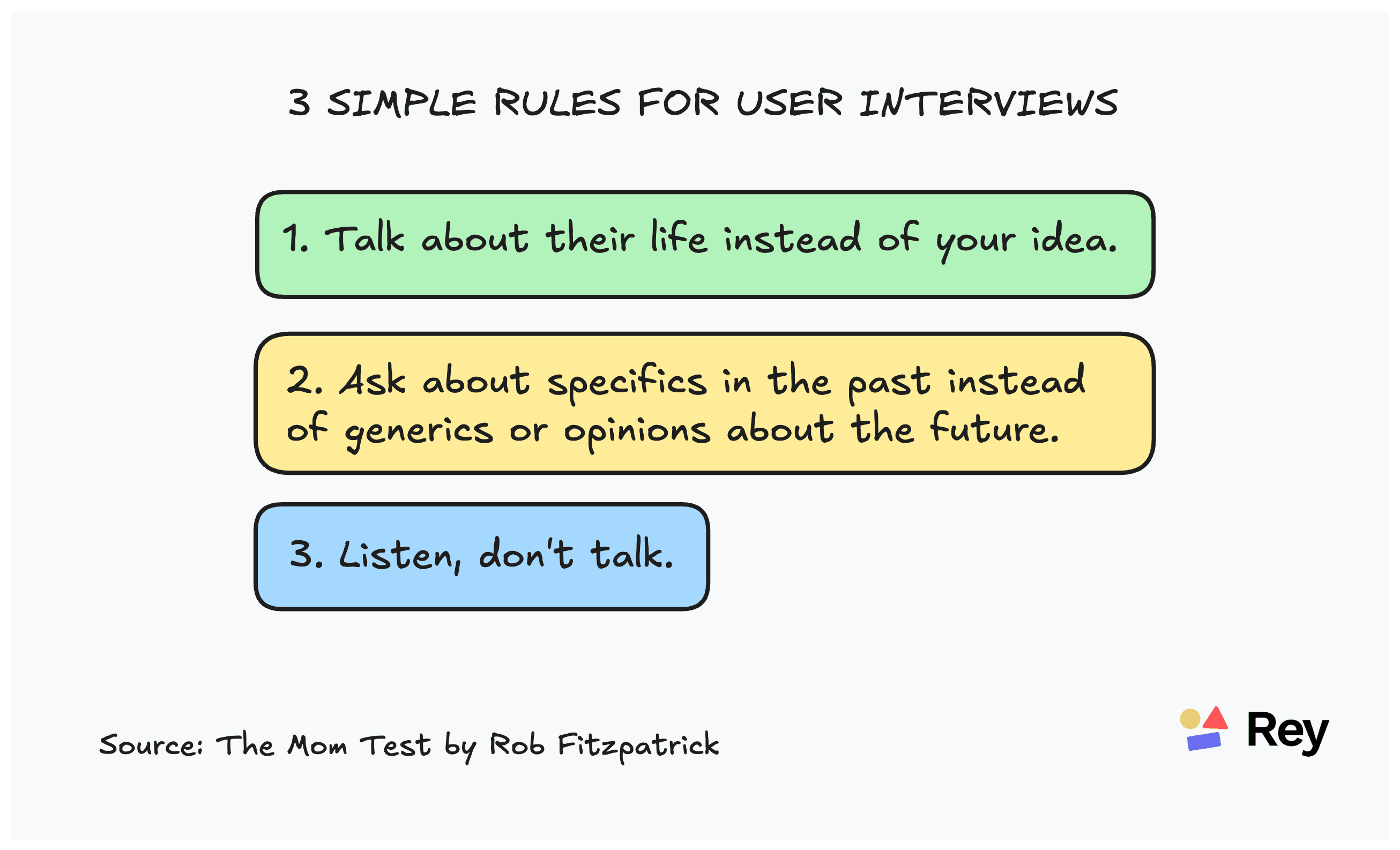

If you want to find more tips and advice on what kinds of questions to ask in these interviews, read The Mom Test. Here are 3 general principles:

Talk about their life instead of your idea. Avoid asking people something along the line of: "Would you use this app that I'm building?" People are generally nice and don't want to hurt your feelings. This is even more so if this is someone you know personally, like your mom or your close friends. Instead of pitching your idea and asking for validation, focus the conversation entirely on understanding their world.

Ask about specifics in the past instead of generics or opinions about the future. Don't ask hypothetical questions like "Would you pay for an app that does X?" Instead, dig into concrete examples from their actual experience.

Say you're building an app to help people better manage their stress and anxiety. You might ask them to walk you through the last time they felt really anxious or stressed out. What did they actually do about it? Talk about what's working for them right now and what isn't. Which apps, therapists, or techniques have they already tried? If they abandoned something, why? Are they currently looking for new ways to cope, or have they pretty much given up? What would need to be true for them to try something new? Where is their stress actually impacting their life - relationships, work, sleep? Have they spent money on solutions before?

Listen, don't talk. Your job in these interviews is to learn, not to convince. Ask open-ended questions, then listen carefully to what they tell you. Pay attention not just to what they say, but to the details that reveal how painful the problem really is and whether they're actively seeking solutions.

Strategy #2. Shadow your users in their natural environment

Instead of interviewing your target users directly, you can also learn a lot by observing them in their day-to-day. Tony Xu and his co-founders discovered the idea for DoorDash by following this strategy in the early days.

When it came to DoorDash, the initial idea really came when we visited a macaroon store owner. Our question that we tended to ask business owners was: "Can we follow you around for a day?" So we'll go and pack boxes with you, do your accounting with you, make salads with you. We wanted to actually feel what it was like their lived experience versus just asking a bunch of survey questions. Sometimes it's very very hard for any customer to tell you exactly what is inside their brain when you ask them what problems they have. And so we wanted to feel and maybe trying to figure it out ourselves.

And it was toward the end of the time we spent with the store manager that she had showed us a booklet of orders she had turned down. All of them were delivery orders. That was the comment and thread. And it just made no sense to us. We said "You're a one-person shop, this is a big deal. This is a thick booklet of orders that probably is very meaningful to you. We don't understand why you're not pursuing it." And so we really just unraveled that thread.

– Tony Xu, DoorDash via Crucible Moments

Regardless of which strategy you choose, focus on learning as much as you can about your target users: their problems, cares, constraints, and goals. Over time, you'll gradually start to build an understanding of the problem space and the gaps in the existing solutions.

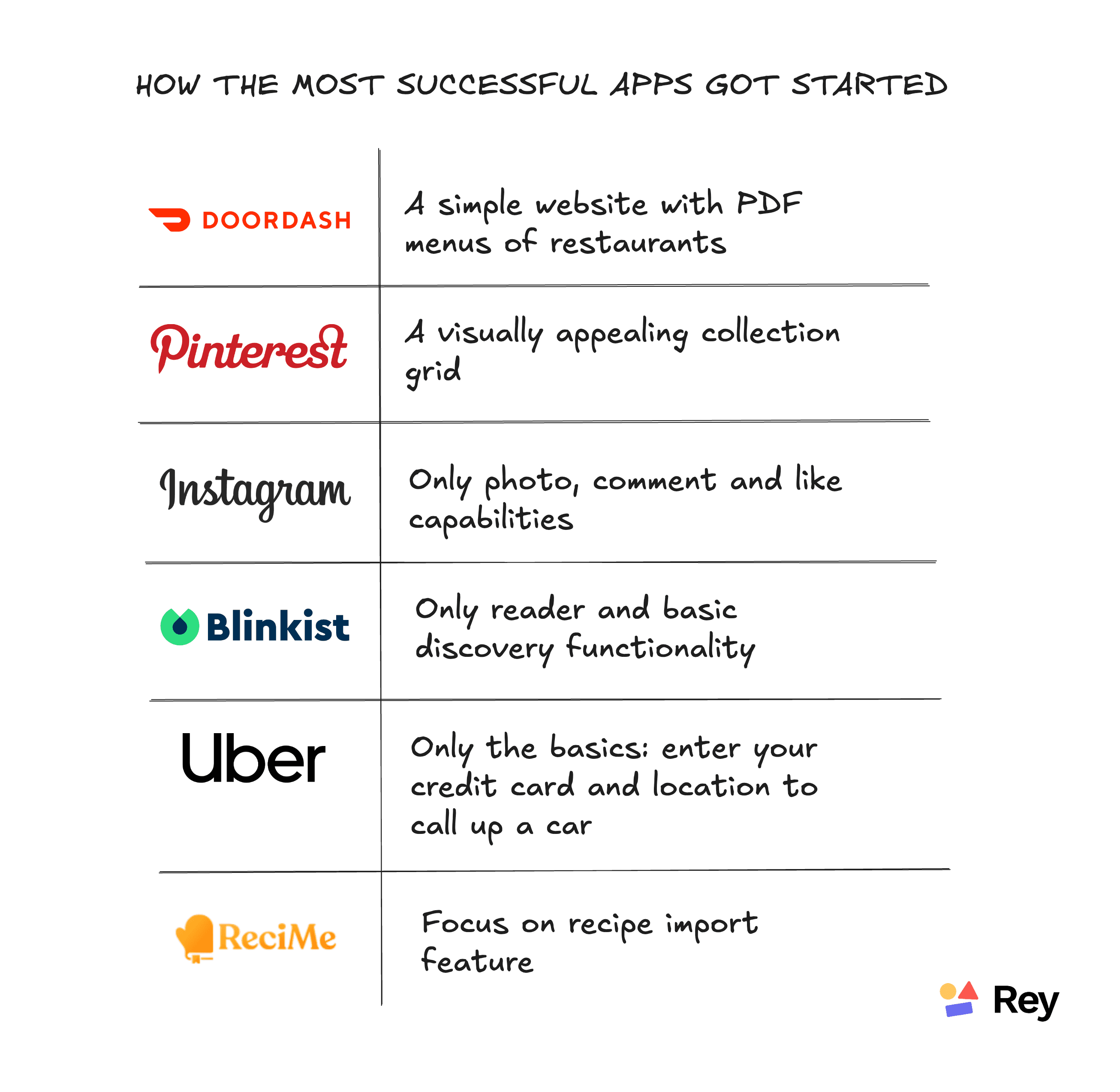

3. Ship the simplest version of your product

Once you feel that you can understand the problem space, build the simplest version of your product that solves for the problem and ship it quickly.

Ask yourself: what's the simplest possible version of this product that I can build today?

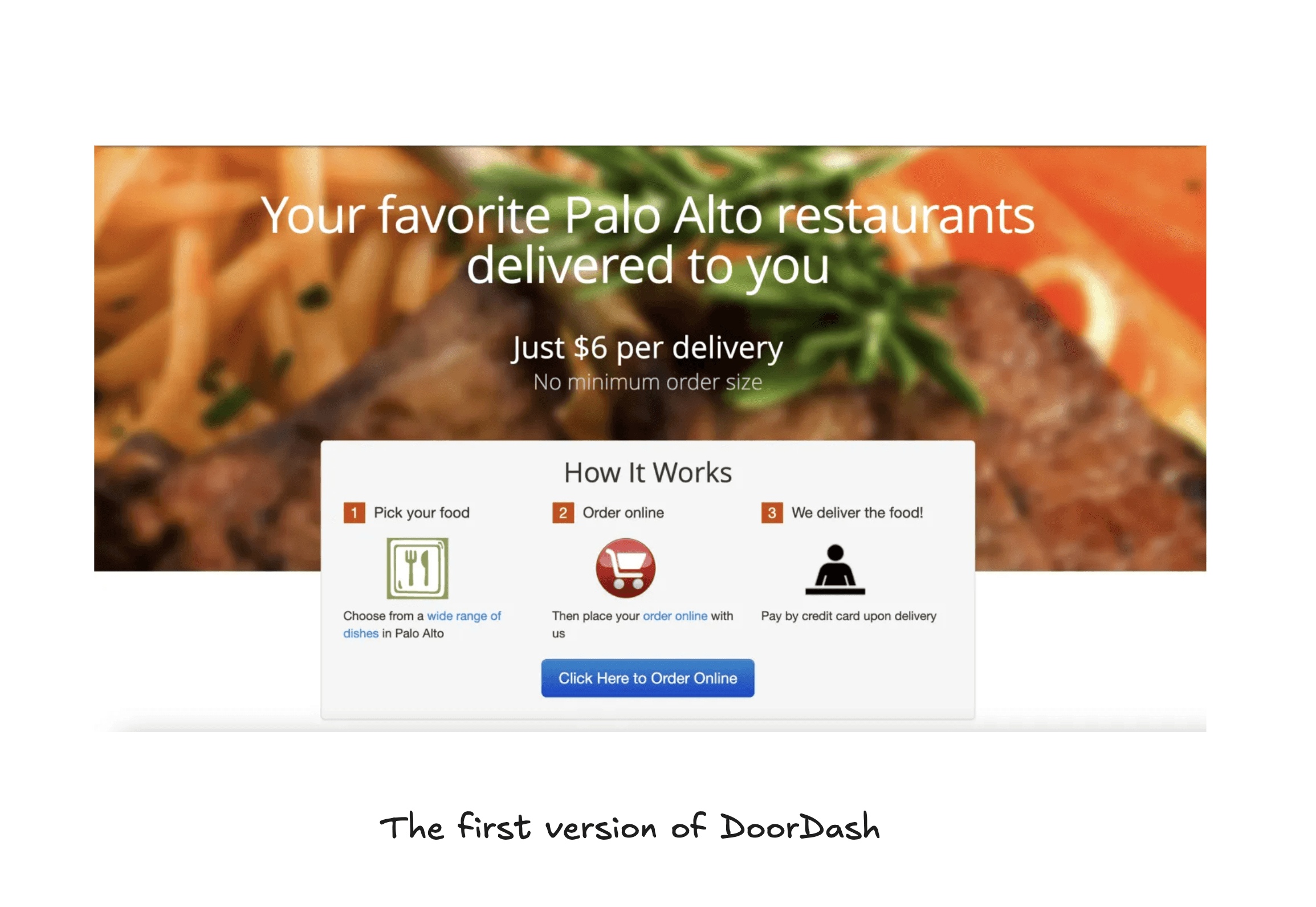

The first version of DoorDash was a simple website with PDF menu of restaurants, and the founders were doing every single delivery themselves. This works because DoorDash focused on delivery in suburban markets rather than densely populated cities. They realized that there's a strong need for delivery in areas where restaurants aren't within walking distance.

"The very first iteration of DoorDash was a website called paloaltodelivery.com with PDF menus of restaurants in Palo Alto. Tony and the team printed a bunch of flyers charging $6 for delivery and put them all over Stanford University. He and the team first wanted to see if there was demand. That was how it all started. A website with PDF menus and flyers."

— Micah Moreau, DoorDash via Lenny's Newsletter

The first version of Blinkist was a simple iOS app with a basic reader and and a list of book summaries. Yet looking back, Holger (one of the co-founders) realized the MVP could even be simpler.

"Perfect MVP for us would have been an email. Signing up for MailChimp, creating a WordPress powered website, attracting people who are interested in this content, learning how to market to those people, learning if they are willing to pay for it, basically learning more about the format using the newsletter format. Then once we got core user base and understood its dynamics, then it would have been the time to develop an app. This only shows how you always learn in hindsight that you should have done things differently."

– Holger, Blinkist via The Starting Idea

Your first version doesn't need to be sophisticated. Whether you're using Rey, other no-code tools, or coding from scratch, think about the simplest possible version you can build. For example, if you're building a meditation app, start with 5-10 guided audio sessions and a simple player. If you're building a recipe organizer, begin with a basic list view and the ability to save favorites.

Focus on one thing and do it exceptionally well

Here's one thing I learned from my decade at Blinkist: It's incredibly hard to get users to adopt your product, unless what you're offering is 10x better than what's been there before.

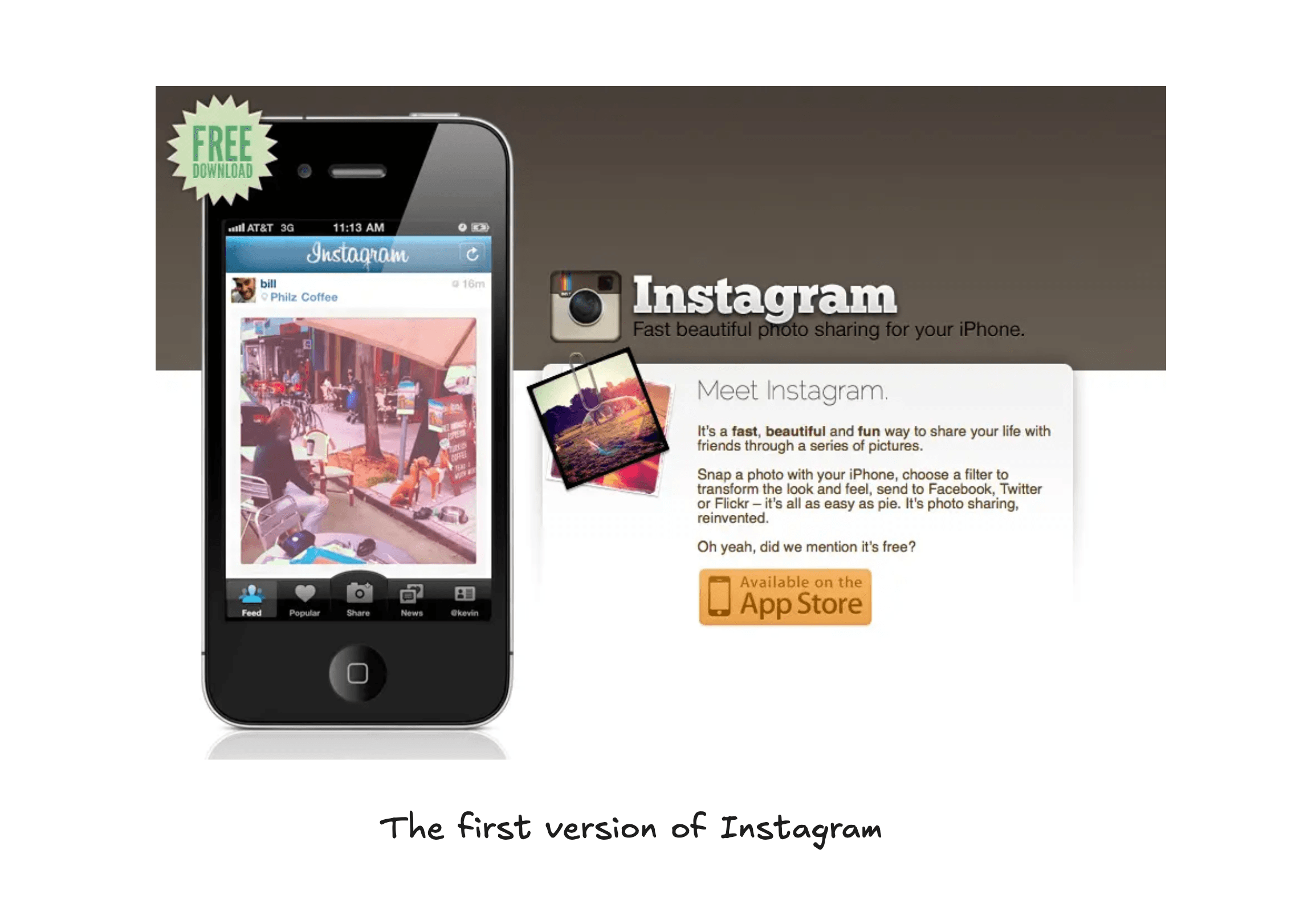

How do you build a solution that's both simple and significantly better? By focusing on the one thing you can do well and iterate on it relentlessly. One mistake first-time founders tend to make at this stage is overloading their first product with features. The founders of Instagram, Pinterest, ReciMe realized they need to do the opposite: focus on the one thing that you believe you can do better than anyone else, and double down on that.

The one thing of Instagram was its photo, comment and like capabilities.

"We wanted to focus on being really good at one thing. We saw mobile photos as an awesome opportunity to try out some new ideas. We spent 1 week prototyping a version that focused solely on photos. It was pretty awful. So we went back to creating a native version of Burb. We actually got an entire version of Burb done as an iPhone app, but it felt cluttered and overrun with features. It was really difficult to decide to start from scratch, but we went out on a limb, and basically cut everything in the Burbn app except for its photo, comment, and like capabilities. What remained was Instagram."

— Kevin Systrom, Instagram via The Cold Start Problem

The one thing of Pinterest was a "really cool" visual grid.

"And we decided that the one thing we had to do really well, if we were going to make a website collection, we had to make it look really cool. Like if it didn't look cool, then no one's going to make a collection because they don't want to show their friends because this thing that they just made looks really lame. So this is the first version of Pinterest. It didn't look very cool. And November 2009, we started building the basic infrastructure and started really iterating on what it could look like. How could we make it look really interesting?

So we went through a lot of versions of this: vertical grid, horizontal grid, both, left side nav, right side nav, top nav, different logos. And we waited until we felt we had something that we thought was really cool. And we would show it to people along the way. We would show them something that we thought was a little bit of an improvement. And we finally felt ready to launch it."

— Ben Silbermann, Pinterest via Startup School

The one thing of ReciMe was the recipe import feature.

"When we first released ReciMe, we built too many things, and none of them worked well. As soon as we realised that our smart importer was our most loved feature, we scrapped everything and re-built our entire app just to drive that one core action.”

— Christine Nguyen, ReciMe via Startup Daily

So focus on the one thing, and do it well.

4. Get users to use your product and iterate

Once you have built the simplest version of your product, reach out to the users that you have talked to and invite them to use the product.

If you're truly solving a problem that your target users are highly motivated to pay for, they will be eager to try out your solution even if it's still early or incomplete.

Optimize for learning over user growth or revenue

At this stage, your goal isn't to make money, but to learn whether you're building something people truly want. Focus on getting people to use your product and understanding their behavior. Are they coming back? What features do they use most? Where do they get stuck or drop off?

The fastest way to learn is to get as close to your users as possible. In Airbnb's early days, Brian Chesky and his co-founders had only a handful of hosts in New York. So each week, they'd make the trip from Mountain View to knock on the doors of every single host and talk to them.

"It’s really hard to get even 10 people to love anything, but it’s not hard if you spend a ton of time with them. If I want to make something amazing, I just spend time with you. And I’m like, "Well what if I did this, what if I did this, what if I did this?"

We’d find out “Hey, I don’t feel comfortable with the guest. I don’t know who they are." "Well what if we had profiles?" "Great!" "Well what do you want in your profile?" "Well I want a photo." "Great. What else?" "I want to know where they work, where they went to school." "OK." So you add that stuff. And then you literally start designing touchpoint by touchpoint. The creation of the peer review system, customer support, all these things came from us literally — we didn’t just meet our users, we lived with them. And I used to joke that when you bought an iPhone, Steve Jobs didn’t come sleep on your couch, but I did."

— Brian Chesky, Airbnb via Masters of Scale.

Ben Silbermann, one of the co-founders of Pinterest, would often sit in coffee shops and ask people to try the service. He realized that what people say they want and what people mean can sometimes be different.

A really common thing that I would ask people, sitting in a coffee shop, I’d be like, "Hey, you know, why don’t you try to create a board or try to pin something?" And then I would ask them to do it, or I’d ask them to look at a button and push it, and right before, I’d say, "What do you expect to see on the other side of that?" And then right after, I’d be like, “Is that what you saw?” And if it was different, I’d be like, "We should fix that up."

— Ben Silbermann, Pinterest via Startup School

Your first users are valuable, so make it easy for them to reach you. Give users your email, your phone number, or set up a dedicated Slack channel or Discord server. Respond quickly when they reach out. Thank them for their feedback. Let them know when you've fixed something they reported or built a feature they requested.

Repeated usage matters more than volume

When Ben Silbermann launched Pinterest to his waitlist of 3,000 users in 2009, there were barely any responses. But he did notice that the few who do end up using it really loved it.

But there was something that was really positive, and it was that the few people that used it, myself amongst them, actually really loved it. And instead of immediately changing the product, I was like, "Maybe I can just find more people like me." And that also fits with our current operating strategy since we don't have very good engineering resources. So we're just going to market this thing. And that's what we started to do.

— Ben Silbermann, Pinterest via Startup School

What you're looking for at this stage is not huge user volume or growth, but a few strong signals that a small group of people out there are using your product and really love it. You'll see this in the data (they're using your product and coming back repeatedly), if they tell you directly, and if you start seeing people telling their friends about your product.

"The founder, Paul Graham, used to have a saying, and it's the most important advice I ever got, and it's what you were saying, and it's counterintuitive. He said, It's better to have 100 people love you than a million people that just sort of like you. If you have 100 people that love your service, when they love something, they'll tell everyone they know."

— Brian Chesky, Airbnb via The Diary of a CEO.

Don't be discouraged if progress feels slow. Every successful founder faced moments of doubt and long stretches where growth felt painfully incremental. Trust the process, stay close to your users, and remember that building something people love takes time.

Once you've seen a strong sign of repeated usage, that means you're seeing early signs of product-market fit. It's time to focus on the next stage: how to launch your app and get your first 1,000 users.

More good reads

How to talk to users (Eric Migicovsky)

The Mom Test (Rob Fitzpatrick)

How the biggest consumer apps got their first 1,000 users (Lenny's Newsletter)

If you have any feedback, questions or want to share your own stories, drop me a line at linh@reyapp.io - I'd love to hear from you.

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe below to get notified when the next one in the series comes out.